ETRUSCAN LIFESTYLEclick for link

Music

What we know of Etruscan music comes to us from the impressions and feelings gained from the many tomb illustrations, or from the mysterious inscriptions on sarcophagus lids. We base our scant knowledge of Etruscan music from the few testimonies which survive from ancient sources, and as far as written score is concerned, there are no examples. Only with the Pythagorean system of the Ancient Greeks can we talk with some certainty of true musical scores, in some cases carved on grave steles, which represent the various Ancient Greek musical traditions. Modern interpretation of such notation is very theoretical and the true values of the musical notes can only be estimated.

Most writers believe, based on the absence of musical manuscripts, that the Etruscans seem to have more of an oral rather than a written musical tradition. On the other hand there is nothing more than circumstancial evidence to suggest otherwise.

The Liber Lintaeus of Zagreb, believed by some to be part of one the Etruscan sacred books, appears to contain certain repetitive rhythmic phrases, which would indicate congregational involvement in the litturgies. Certain tablets found in Etruscan tombs also show rhythmic patterns, indicative of poetry or verse. Those sources together with tomb illustrations showing numbers of musicians playing together, and accounts by Livy of Etruscan theatre tend to lend credence to the viewpoint that such elaborately planned events may have had rehearsals possibly utilising written scores.

The important role of music in all significant aspects of life: banquets, religious celebrations, funeral rites; and its asscoiation magical and spiritual aspects tend to add weight to this argument.

Music accompanied both work and leisure activities. Solemn ceremonial events such as the games of the annual Fanum Voltumnae were accompanied by professional Musicians and dancers as attested by Titus Livius. It featured during sporting competitions, and military drills, during hunting and funeral activities, as well as providing background ambience during the banquets that went on within the walls of the sumptuous palaces of the aristocracy. But this music was played not only during the meal itself (SYNDEIPNON), but also while the food was being prepared and of course during the long convivial drinking sessions spent after meals (the origin of the term SYMPOSIUM).

During the funeral ceremony, the sweet inviting sound of the Auleta (flute) and lyre, would lighten the atmosphere of the banquet, persuading participants to dance. We know little of the original Etruscan names of the musical instruments and therefore use the Latin or Greek names instead. We can classify them in their various groupings:

Percussive instruments such as Bells, Campanella (Tintinnabulum) and castanets (crotalus) are found, such instruments easily carried by young dancers.

From Pliny the Elder's description of the tomb of Lars Porsenna, we can draw some interesting conclusions. As with many other objects with Apotropaic function, bells were mounted on the tomb with the objective of producing sounds when they were moved by the wind, thus repelling evil presences.

Stringed instruments:

Lyres, usually with seven strings (Heptacord).

Kithara or Barbitones.

Lyres can be divided into two types: Those where the sound box was made of the shell of a turtle (lyra and barbitos) and those made of wood (kithara and phorminx). In Ancient Greek times, the Lyrae and Barbitos were used by amateur musicians, the kithara and phorminx by professionals.

According to Greek mythology, the invention of the lyre is attributed to Hermes. When Hermes was one day old, he climbed out of his cradle and found the shell of a turtle. He stretched the pelt of a cow around it, fixed the two horns through the leg holes of the turle and tied strings across it.

One day, when Hermes stole some sheep from Apollo, the latter was soothed by the sound of the instrument. Hermes escaped punishment and the instrument gained its divine status.

Wind instruments

The Tuba was a straight trumpet made out of copper or iron. It was a long tube with a length of about 120-140 centimeters finishing in a bell shape. In its usual form (from later Roman models) it came in 3 parts with a mouthpiece. The origin is Etruscan and has many similarities with the Greek Salpinx. The difference between these two is that the end of the tube of the salpinx had the form of a tulip. They were both used in the army and during games. The objective was to sound as loud as possible. The sound of it according to Ennius invoked fear and panic in the minds of enemies: "at tuba terribili sonitu taratamtara dixit". As in later Roman times, the tuba was used at sacrifices, triumphal processions and funerals. However its main purpose was to give signals for tactical movements during battle.

The Lituus - The term Lituus has two meanings: A crooked staff, usually held by powerful individuals in the religious and political arena, and often used to trace signs in the sky or on the ground for ritual division purposes"; but it was also an L-shaped wind instrument. The instrument was usually made of bronze and could be up to 160 cm long.

The Cornu (from the Latin "horn"), was a coiled brass instrument, often of huge diameter (in Pompeii an example was found with a diameter of 150 cm). It was probably coiled so that it could be worn across the shoulders (Its possible origins was for the hunt, but in later years it became an instrument of ceremony). Its longer length gave it more musical versatility than the tuba

The Tibia: a type of flute. According to Livius, the Tibia was played by Etruscan musicians during the Ludi Scenici, organised during the fourth century BCE to counter the great plague of Rome.

The Aulos or double flute, which could almost be called the Etruscan national instrument had two divergent flute-pieces attached to a double mouthpiece, often fixed to the lips of the player by means of a Capistrum, or a strap around the head. The virtuosity of Etruscan flautists was almost legendary among the Greeks and Romans. Timaeus, writing in the fourth century BCE, gives us an account of how the Etruscans made practical use of the entrancing and melodious graces of the Etruscan flute to lure wild boars out of the wilds only to be caught by waiting huntsmen.

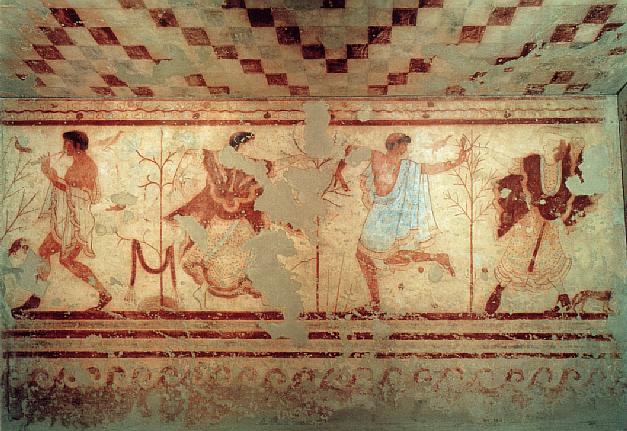

Examples of Etruscan performers can be seen  vividly portrayed on the walls of the Tomb of the Triclinium in Tarquinia.

vividly portrayed on the walls of the Tomb of the Triclinium in Tarquinia.

While the Musicians work their musical magic, The dancers, depicted in an Idyllic landscape move with subtle expressive movements, wearing diaphanous veils or colourful cloaks (Tebenna) often knotted on their shoulder, or folded in the hands, similar to modern day dancers from Ionian Greece.

Music often accompanied the rhythmical movements of dancers, whose dance was not just for entertainment, but in some cases was linked to various rituals including funeral celebrations.

Music was also used in the Etruscan performing arts. As well as mime, the Etruscans gave theatrical performances with the various dramatis personae represented by masked histrioni, or theatrical performers. From the 4th Century BCE, there was considerable influence by Greek theatre.

Fashion

In the 7th century BCE, Etruscan clothing was very similar to that of the Greek archaic period. The men in the archaic age wore a kind of robe, which was knotted at the front. In later times this gave way to the "tunica" which was worn over the head, usually with a colourful cape slung over the shoulders. This cape, usually wide and heavily embroidered, became the national costume of Etruria - the "tebenna", later to become the Roman toga.

In the 7th century BCE, Etruscan clothing was very similar to that of the Greek archaic period. The men in the archaic age wore a kind of robe, which was knotted at the front. In later times this gave way to the "tunica" which was worn over the head, usually with a colourful cape slung over the shoulders. This cape, usually wide and heavily embroidered, became the national costume of Etruria - the "tebenna", later to become the Roman toga.

Women wore a long tunic down to the feet, usually of light pleated material and was typically decorated on the edges. Over this was worn a heavier colorful mantle.

The most common types of footwear were high sandals, ankle boots and one characteristic type of shoe, with upward curving toes, possibly of Greek or Oriental origin.

The most common types of footwear were high sandals, ankle boots and one characteristic type of shoe, with upward curving toes, possibly of Greek or Oriental origin.

The most common head wear was a woolen hat, but these came in many different forms such as caps, conical type hats, pointed hoods and wide brimmed hats, such as are still worn to this day by Tuscan farmers. Often the hat identified the person that wore them with a particular social class. From the end of the 5th century BCE, it became more common not to wear a hat. Also from the 5th century BCE men, who previously wore a beard, began to shave and to wear short hats. The regalia of later Roman times, such as the purple robes worn by the emperors, were of Etruscan origin, as were a number of symbols often ascribed to Rome such as the Lictor and Fasces.

The regalia of later Roman times, such as the purple robes worn by the emperors, were of Etruscan origin, as were a number of symbols often ascribed to Rome such as the Lictor and Fasces.

Women wore a great variety of hairstyles including long, shoulder length, knotted or interlaced behind the shoulders, in later times, the hair was worn shorter, and was knotted at the crown of the head or collected in gauze mantles or caps.

The magnificent robes of the patrician women were finished off with exquisite jewellery including ear-rings, necklaces, bracelets and fibulae. In its time, Etruscan Jewellery was unsurpassed by any other in Europe.

The bronzes of Etruria were equally celebrated throughout Europe, North Africa and the middle East.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento